I predict the forecasters will be wrong

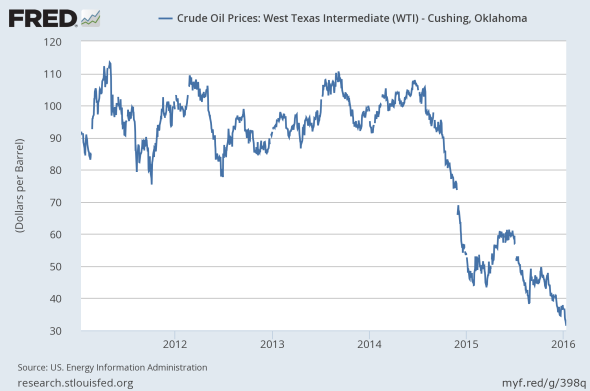

Posted: January 21, 2016 Filed under: Economics, Finance, Oil, Statistics | Tags: finance, forecasting, Oil, wall street Leave a commentRecently, the price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) Crude Oil dropped to below $30. Just 18 months ago, the price was over $100.

Here is the price of oil over the last 5 years:

It’s worth thinking about whether anyone saw this coming.

Earlier last year, after the initial and huge drop in the price of oil to below $50, there was a very interesting article in Bloomberg about how wrong most forecasters were in their predictions on oil. They extrapolate from the present in ways that presume a certain stability in the world that does not exist. In the Bloomberg article, the actual price of oil was half that of the lowest Wall Street estimate.

How have they been doing since? Of the analysts surveyed, the lowest had oil somewhere around $50, a full $20 higher than where it is now. And the median estimate was closer to $70.

In April, having observed the huge declines, the professional forecaster, despite some useful knowledge of individual energy companies and OPEC, did not fully appreciate that China’s economic growth might slow, resulting in substantially less oil demanded; that a deal with Iran might come to be, resulting in more oil on the world markets; that Saudi Arabia would refuse to cut output and instead prefer to take market share, further increasing the supply of oil.

This is not unique to oil, as you might guess. At the beginning of 2015, experts had also expected continued gains in the stock market on the order of 8%, similar to what had occurred in 2014. Instead, the S&P 500 dropped 0.7%.

The world is a complex place, and it is difficult to admit that we cannot know the ways in which things will turn. But Wall Street experts continue to believe that they can predict the world’s events. It seems even the most pessimistic of the professional analysts could not have foreseen the size of the drop in oil. Similarly, following the Great Recession and the tremendous stock market declines, most could not foresee the massive stock market rally.

Over a number of years, researchers at Duke collected over 11,000 surveys in which CFOs of large corporations were asked to forecast the S&P 500 index’s return for the following year. Not only did their forecasts (or point estimates) have zero predictive value, but the CFOs also provided 80% confidence intervals. Anything outside of this area would be deemed a surprise (or an outlier). If they had constructed accurate confidence intervals repeatedly, the actual returns would occur outside of their intervals roughly 20% of the time. In truth, this occurred 67% of the time.

At the start of a new year, I find it useful to remind myself to discount experts’ advice, especially when it is provided on the basis of authority alone: try to assess the argument rather than the self-confidence.